Shot types and immunities

Written by Aaron Hammond

05.03.2023

Talking about vaccination can be tough. People often use imprecise terminology. Computers don't, but they need to be taught.Before we try to teach the computer, let's define some terms for sanity.

What’s in this needle, anyway?

Different jurisdictions typically write their requirements for immunization in terms of a dozen or so high-level immunization types. These describe protection against a specific disease or illness, and most mandate several doses in a series that may span the student’s entire school career.

We track state requirements for twenty kinds of required vaccinations or immunization types. As recent history proves, new entries may be added to the list.

Grouping for readability, we monitor the following immunization types:

- COVID-19 and Influenza

- Diptheria; Tetanus; and Pertussis

- Hepatitis A and Hepatitis B

- Haemophilus influenza type b (HiB)

- Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

- Meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY) and Meningococcal B (MenB),

- Measles, Mumps, and Rubella

- Pneumococcal Conjugate (PCV) and Pneumococcal Polysaccharide (PPSV)

- Polio, Rotavirus, Varicella, and Zoster (shingles)

That's a lot of shots!

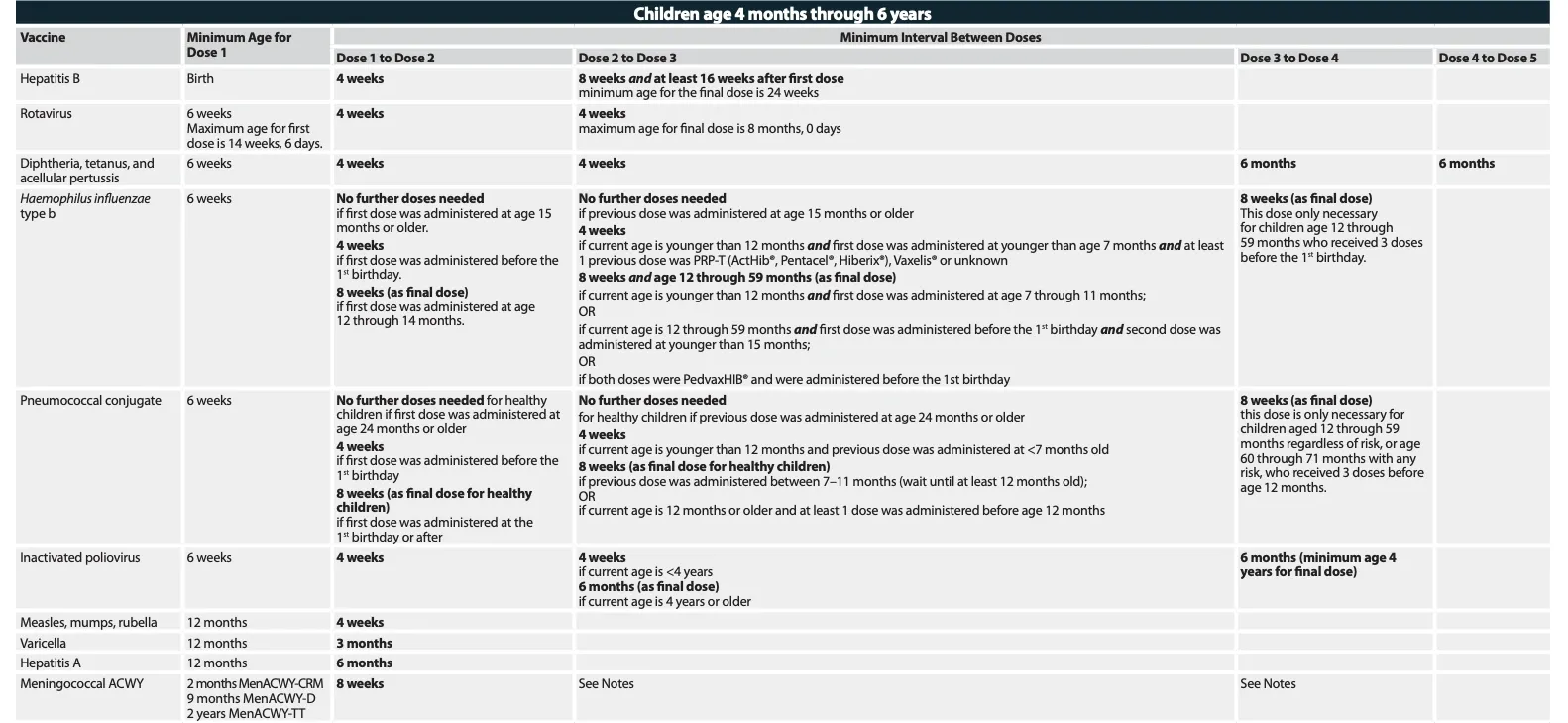

Immunization requirements in schools have expanded considerably in the last half-century. The number of discrete dosage events needed over a student’s school career has grown. It’s impractical to visit a practitioner dozens of times to satisfy the requirements for each series and booster independently. For efficiency, multiple boosters for separate series are frequently administered in one appointment. Practitioners can batch these dosage events within the timeframes prescribed by state law.

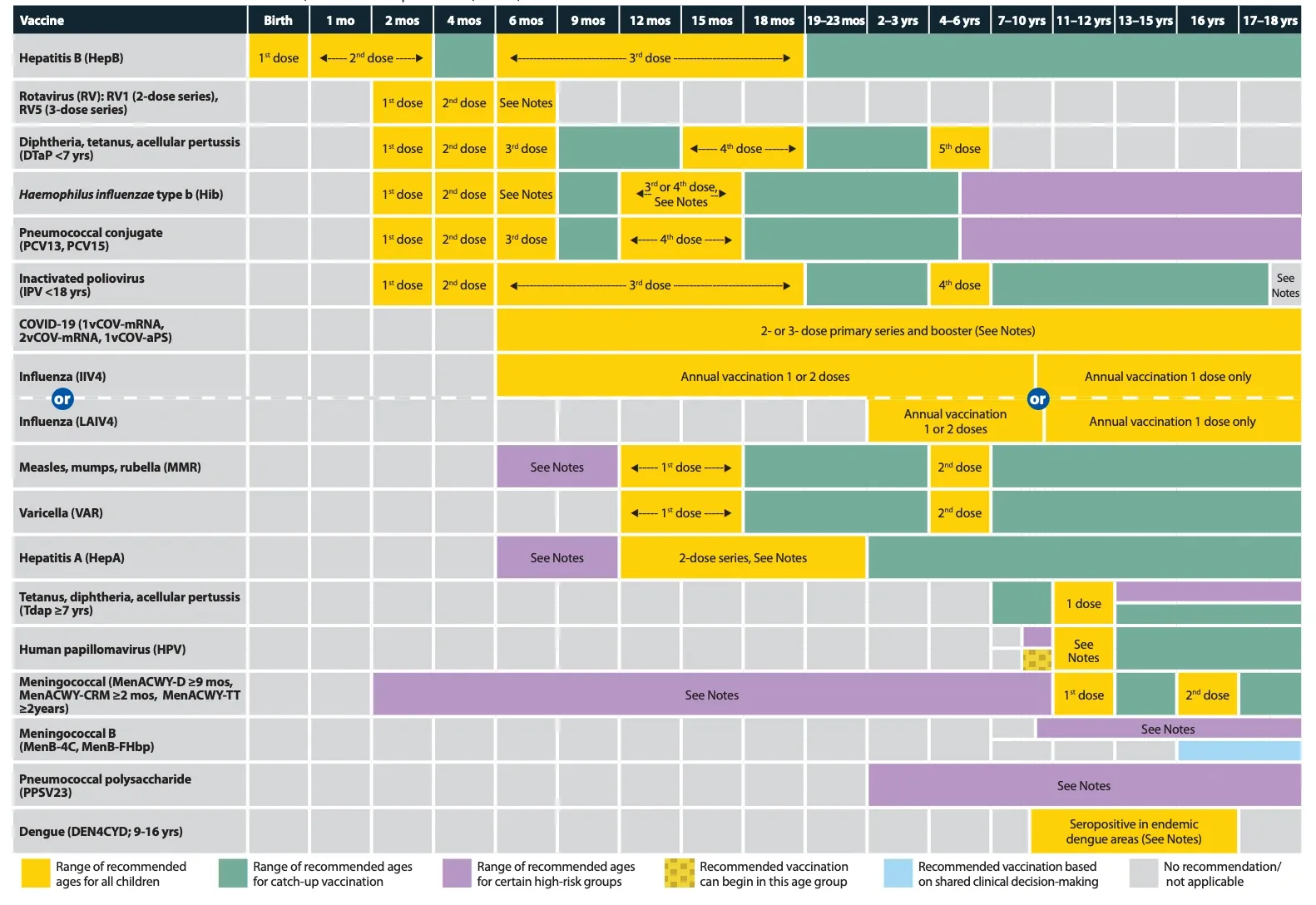

The CDC recommends the above vaccination schedule for children and adolescents. Each state mostly follows some number of these rules, but often there are small, subtle deviations. This ambiguity can distress engineers.

However, most children don’t like sitting through several shots in quick succession. As common practice converged on popular configurations of immunization schedules, the industry developed novel products to meet this demand. New formulations combine agents to boost immunity against several childhood diseases, reducing the number of distinct shots a student will receive over their childhood.

Two-for-one

Consider the MMR vaccine. This popular formulation combines measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines in one inoculation. Almost every student in the United States receives this compound shot today, but the constituent vaccines were each developed independently and mandated by states over time.

Sometimes, a student may receive a vaccine for just one of these viruses instead of all three. An immunization schedule valid in one state may become non-compliant when a student moves to another jurisdiction. This frequently happens for international students and immigrants, but even crossing state lines domestically can pose headaches for parents.

The CDC recommends minimum time intervals between doses of each vaccination. Students without required immunizations must show progress toward compliance to continue attending school. Receiving a dose too early doesn't usually affect compliance.

When families move from states with fewer immunization requirements to those with more rules, students often need to “catch up” on their immunizations. This requires some creativity from practitioners to fit and space series correctly. In these cases, a student may receive the typical dose of MMR as a toddler and then some combination of separate shots against measles, mumps, and rubella when mandated in the new schedule.

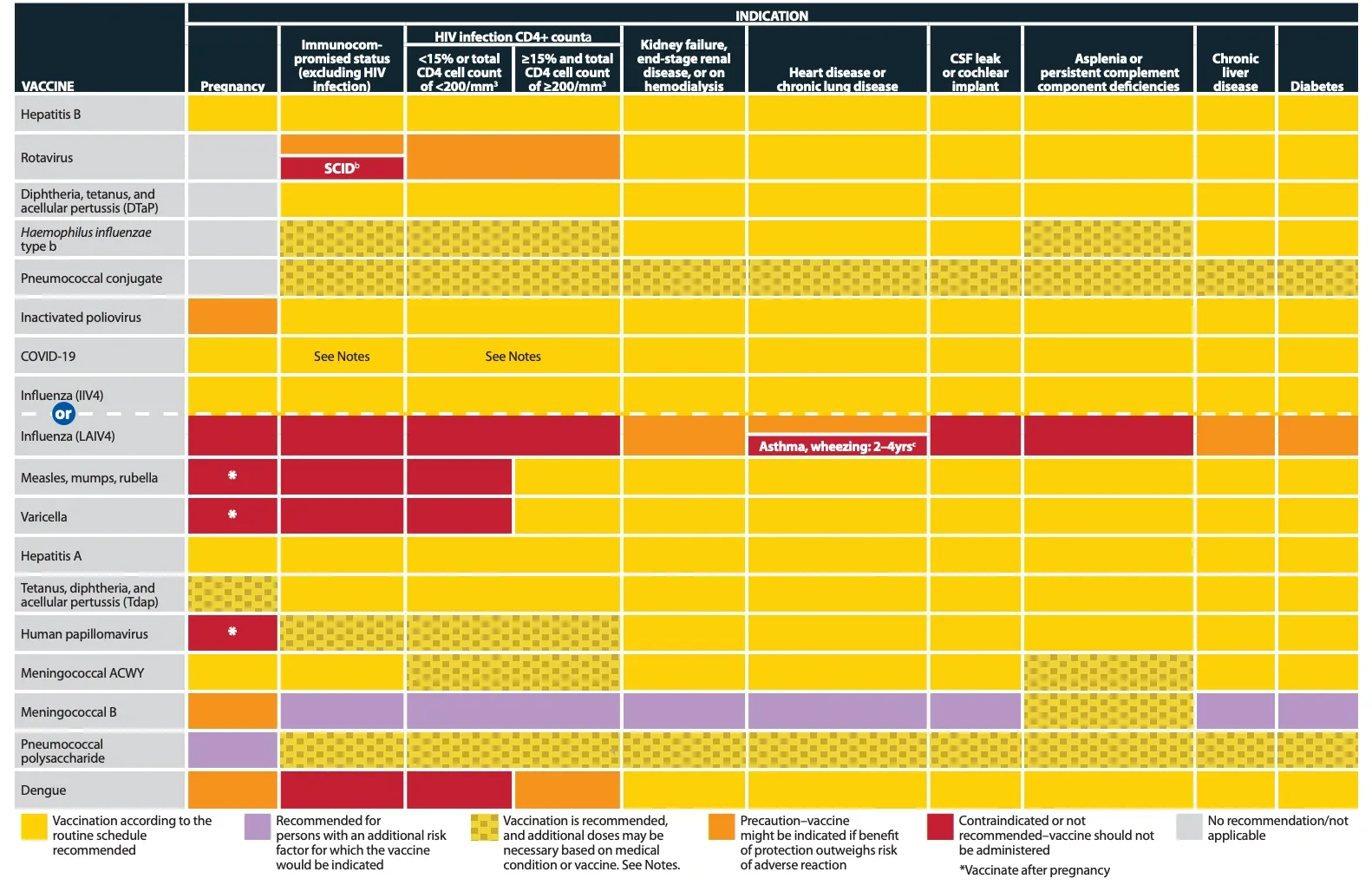

Similarly, suppose a student is allergic to some ingredient in only one of the three component vaccines. In that case, they will receive separate shots for the remaining two instead of the usual triplet. Some health conditions may exempt a student entirely from a required immunization type.

Over the last two decades, states added requirements for vaccination against varicella, the virus that causes the childhood infection commonly called chickenpox. This vaccine is administered and boosted around the same ages as MMR, sometimes even in the same appointment. The MMRV vaccine combines the MMR and Varicella vaccines in a single shot, extending the prior synthesis of measles, mumps, and rubella.

The CDC recommends the vaccination schedule above for children and adolescents with any of the listed medical indications. Attitudes toward medical exemptions from vaccine requirements have shifted considerably in recent years, and state laws have followed. We observe that exemption is the most polarized dimension in the differences between state rules.

Threading the needle

As a former child myself, I applaud fewer shots! It does, however, complicate our calculation of compliance.A single shot may satisfy requirements for multiple immunization types. Paper immunization records are usually presented in terms of dates the actual shots were administered instead of the requirements each satisfies. Vaccines are specified by their shot type, a label uniquely identifying a specific formulation of an authorized or future vaccine.When detecting a shot date on the page, we must be precise about the type of shot. It isn’t enough to see a date next to the word measles to decide if it satisfies the measles requirement. We must detect whether that word is part of a bigger phrase, like measles, mumps, and rubella. Fortunately, Karp-Rabin is great for this kind of thing!

What's next

To use Karp-Rabin, we must find an efficient way to detect a single shot type inside a text fragment. Using the list of shot types as a "haystack," we find the "needle" shot type that most closely matches an input text.